“Níl Aon Tintéan Mar Do Thintéan Féin.” (Old Irish proverb; literally: there’s no fireplace like your own fireplace).

The intention of this AAR, only my second game of V2, is to establish an autonomous Ireland, removed from English influence entirely if possible. Some necessary editing was required in order to create this historical scenario: I began a game as Britain, immediately giving Ireland independence and switching to Ireland at that point.

I hope to maintain a separate, but nominally friendly stance from the British and maintain neutrality in European affairs, where possible. The foundation of a suitable defensive army and a strong navy is also an aim, along with the establishment of overseas colonies, possibly in America or Australasia, to achieve the final aim of ending 1935 with at least secondary power status- but hopefully much more.

Prologue.

The Irish House of Commons

In 1833, following years of agitation on the part of the Catholic majority in Ireland, a group of Irish landowners and their backers at Westminster met with British and Irish MPs in London to discuss matters of mutual interest. These matters were, namely, the reestablishment of the Irish Parliament. Motivated by power and the opportunity to impart their own, often conflicting, local influence to their benefit, these men would sow the seeds of what was to become the Free State of Ireland.

Earl Grey,and subsequently Lord Melbourne, following the Abolition of Slavery Act began to look at establishing a more subtle approach to controlling the Westernised satellites of the Empire. The obvious disenchantment of the Irish would be a stumbling block to further expansions in Asia, with British military and political resources being diverted to constantly settle disputes in Ireland.

What was proposed was a closely monitored Home Rule for the island of Ireland, which would allow the state to establish its own police and militia force, as well as a small flotilla to safeguard fisheries. Middle and upper class voters would elect a Lower House, while the upper strata of British landowners and capitalists would sit in the Upper House, or Senate.

The Upper House would have final say on all non-domestic policy and major social or political reforms. The Senate was to act as a controlling influence on Westminster’s behalf, should the Lower House transgress the interests of wider British policy.

Following the fall of Melbourne that Winter, Wellington and then Peel indicated that they would not follow through with the Home Rule for Ireland Bill, however, in the upheaval following the fire at Westminster palace, a delegation of both Catholic and Protestant Irish landowners, lead by Lord Alfred Leith, convinced leading Tories that the Upper House would guarantee Irish loyalty to the crown.

Peel was by now embroiled in a bitter dispute with China over their territorial expansions in Asia and the relative calm of the Irish peasants in recent years lead to his preliminary approval of the plan.

In the Spring of 1835, the Government of Ireland Act was passed by both the Houses of Commons and the Lords. Certain accounts have it that the coffers of some of the wealthier and more influential Anglo-Irish lords were opened and promises of commercial and political influence in the newly-founded state helped to ease passage of the bill.

Ireland's infrastructure and natural resources (1836)

The Lower House was lead by Brian Roberts-Rowe of the Conservative Party, while Lord Leith was elected leader of the Senate, a position that ennobled him as Consulate for Westminster, the King’s man in Ireland, for all intents and purposes.

That April saw the victory of the Whigs at the polls in Britain and with it Melbourne and his more lenient attitude to Irish domestic autonomy.

Chapter: 1: The Sun Rises from the East.

1st January 1836: The British, already engaging with border disputes with Chinese warlords, formalised the conflict with a declaration of war. A massive blockade of Chinese ports ensued. The Irish government used this opportunity to pass wider tax reforms, allowing for the taxation of the Irish people by their elected representatives. Liberal MP’s balked at the empty rhetoric of the Conservatives, suggesting they had replaced the Imperial hegemony of Britain with a financial same of landlords of Anglo-Irish stock.

1st Jan 1837: It has been a year since Ireland became a Free State. The Munster and Leinster Armies have been established, the latter under the command of Francis O’ Leary, son of Sir Edmund O’Leary- a prominent Liberal lord.

From the diary of Peter O’Manhony, civil servant in Dublin Castle: 1/1/37 “Politically, the country remains calm, a collective relief abounds after the political upheaval of the preceding decade. A controversial law passed by a local council in February of this year, which forbade Britons settled in Londonderry from building on their own private lands was perhaps the only moment of controversy. It was a fleeting reminder of the tensions that flow beneath the surface both here and across the Irish Sea. The stationing of a garrison in Glasgow, looked ominous, particularly so as the British didn’t bother to hide their manoeuvres. There may be an ulterior motive to their granting us these liberties...”

May 1837: The government is pleased to report that a positive balance of trade has been fostered with exports of fish, cattle and fertiliser outstripping our imports of fruit, wool and grain. The improvement of our military doctrines continues.

1st Jan 1838: A tax increase was levied against the middle and lower classes in order to fund new education and administration initiatives on the part of the Conservative government. The state’s first ship “Lady Wicklow”, a steamer built in Dublin, arrived to great jubilation in the port of Cork on October 6th, the very day that a truce was declared between Britain and China. Reactionaries and liberals both made slight gains in the Senate, but nothing that could possibly trouble the “Blue Majority” as commentators have taken to calling the Senate.

The 1838 Potato Blight

July 1838: Potato blight has struck county Donegal and the government quickly steps in to assuage any panic and to tend to those affected- mostly poor Catholic farmers. However, word travels quickly of the blight and Ireland suffers a loss of prestige, with one Minister in Westminster remarking that “[The Irish] can’t even grow potatoes correctly when we are not there to help.”

Chapter 2: Succession and Democracy.

The years of 1838 to 1940 saw many changes both within and without. Queen Victoria was crowned in 1838, with both Prime Minister Roberts-Rowe and Lord Leith in attendance. Observers remarked at the obvious tension between the two men, uncomfortable in each other’s presence outside of diplomatic events. Rumours persist at home of blazing conflicts between the Irish-born Roberts-Rowe and Scottish-born Leith over the handling of the Donegal blight. A definite fracture was developing in the Conservative party. Liberals gained in the Upper House in both ’39 and’40.

On the European front, Prussia and Austria went to war, with Prussia demonstrating diplomatic nous by making peace with several of Austria’s allies before blood was shed.

The 1st of January 1840 saw the beginning of the election in Ireland- the first election after Home Rule passed. The divisions in policy (and some claimed, loyalty) in the Conservative Party lead to their shock defeat at the polls. Roberts-Rowe was succeeded as Prime Minister by Daniel O’ Connell, the man known as “The Great Emancipator” for his success in obtaining Catholic emancipation in the late 1820’s.

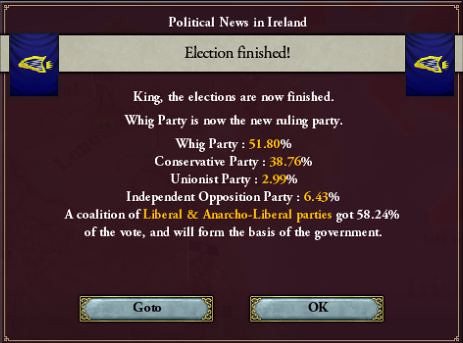

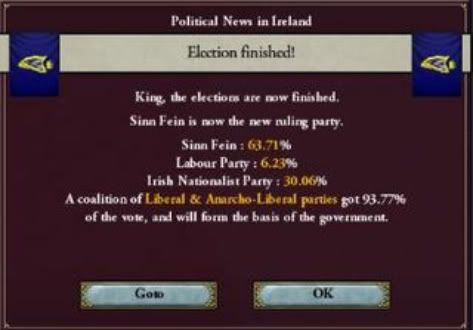

The 1840 election results

The new Whig government (a coalition of Liberal and Anarcho-Liberals) inherited a very healthy Finance Ministry. Exports of farming products were accelerating and the Bank of Ireland was now lending to several prominent nations in Europe. Capitalists, however, were finding it difficult to establish themselves, due to several factors, not the least of which was the vast majority of the available workforce were farmers or soldiers.

Chapter 3: “The Great Emancipator.”

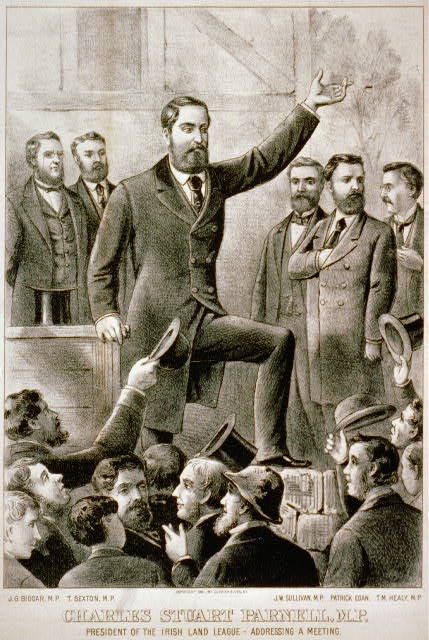

Daniel O'Connell

The first term of O’Connell saw financial stability, particularly in the face of British belligerence around the globe- wars with Spain, France and China (once more) lead to concern that Ireland’s military potential would be threatened by other smaller nations. Though still firmly a satellite of Britain, the Irish had eyes on greatness. O’Connell set projects in Ulster and Leinster to advance industrialisation, particularly encouraging the construction of a glass factory. Looking on with little stature at Great and Secondary Powers colonising far-flung continents only hastened the government’s attempts to elevate Ireland.

From the diary of Peter O’Manhony, civil servant in Dublin Castle: 11/2/44

“I was over-joyed to receive a letter from my dear friend Cathal Donnelly, who has returned from the Colonies in India to take charge of the 1st Leinster Battalion. A greater soldier and leader cannot be found in this island or the next and his promotion to headquarters in Dublin suggests that we will be sharing a drink or six soon... “

“My department had to deal again with an outbreak of potato blight in Donegal, which we have been instructed to hush up about. The reoccurrence of the blight is a very discouraging thing, and one that I shall have to keep abreast of.”

“No sooner had the last one uprooted the Blues, another election has been called for December. The Conservatives are talking of amalgamating my Department of Administrative Affairs with Commerce and Agriculture, but I believe that to be mere hot air.”

Indeed, the election was to prove another triumph for O’Connell, who increased his party’s share of seats to 58%, roundly trouncing the Conservatives. As 1844 closed and 1845 dawned, the foundations for factories were finally being laid. Pro-business policies from the very beginning were now coming to fruition as the Capitalist entrepreneurs began to industrialise Ireland. With a population of just over eight million, O’Connell knew that Ireland’s fishing industry and potential colonies would be needed in the coming years to ensure Ireland standing space on the world stage. The future lay over the horizon, at sea.

The intention of this AAR, only my second game of V2, is to establish an autonomous Ireland, removed from English influence entirely if possible. Some necessary editing was required in order to create this historical scenario: I began a game as Britain, immediately giving Ireland independence and switching to Ireland at that point.

I hope to maintain a separate, but nominally friendly stance from the British and maintain neutrality in European affairs, where possible. The foundation of a suitable defensive army and a strong navy is also an aim, along with the establishment of overseas colonies, possibly in America or Australasia, to achieve the final aim of ending 1935 with at least secondary power status- but hopefully much more.

Prologue.

The Irish House of Commons

In 1833, following years of agitation on the part of the Catholic majority in Ireland, a group of Irish landowners and their backers at Westminster met with British and Irish MPs in London to discuss matters of mutual interest. These matters were, namely, the reestablishment of the Irish Parliament. Motivated by power and the opportunity to impart their own, often conflicting, local influence to their benefit, these men would sow the seeds of what was to become the Free State of Ireland.

Earl Grey,and subsequently Lord Melbourne, following the Abolition of Slavery Act began to look at establishing a more subtle approach to controlling the Westernised satellites of the Empire. The obvious disenchantment of the Irish would be a stumbling block to further expansions in Asia, with British military and political resources being diverted to constantly settle disputes in Ireland.

What was proposed was a closely monitored Home Rule for the island of Ireland, which would allow the state to establish its own police and militia force, as well as a small flotilla to safeguard fisheries. Middle and upper class voters would elect a Lower House, while the upper strata of British landowners and capitalists would sit in the Upper House, or Senate.

The Upper House would have final say on all non-domestic policy and major social or political reforms. The Senate was to act as a controlling influence on Westminster’s behalf, should the Lower House transgress the interests of wider British policy.

Following the fall of Melbourne that Winter, Wellington and then Peel indicated that they would not follow through with the Home Rule for Ireland Bill, however, in the upheaval following the fire at Westminster palace, a delegation of both Catholic and Protestant Irish landowners, lead by Lord Alfred Leith, convinced leading Tories that the Upper House would guarantee Irish loyalty to the crown.

Peel was by now embroiled in a bitter dispute with China over their territorial expansions in Asia and the relative calm of the Irish peasants in recent years lead to his preliminary approval of the plan.

In the Spring of 1835, the Government of Ireland Act was passed by both the Houses of Commons and the Lords. Certain accounts have it that the coffers of some of the wealthier and more influential Anglo-Irish lords were opened and promises of commercial and political influence in the newly-founded state helped to ease passage of the bill.

Ireland's infrastructure and natural resources (1836)

The Lower House was lead by Brian Roberts-Rowe of the Conservative Party, while Lord Leith was elected leader of the Senate, a position that ennobled him as Consulate for Westminster, the King’s man in Ireland, for all intents and purposes.

That April saw the victory of the Whigs at the polls in Britain and with it Melbourne and his more lenient attitude to Irish domestic autonomy.

Chapter: 1: The Sun Rises from the East.

1st January 1836: The British, already engaging with border disputes with Chinese warlords, formalised the conflict with a declaration of war. A massive blockade of Chinese ports ensued. The Irish government used this opportunity to pass wider tax reforms, allowing for the taxation of the Irish people by their elected representatives. Liberal MP’s balked at the empty rhetoric of the Conservatives, suggesting they had replaced the Imperial hegemony of Britain with a financial same of landlords of Anglo-Irish stock.

1st Jan 1837: It has been a year since Ireland became a Free State. The Munster and Leinster Armies have been established, the latter under the command of Francis O’ Leary, son of Sir Edmund O’Leary- a prominent Liberal lord.

From the diary of Peter O’Manhony, civil servant in Dublin Castle: 1/1/37 “Politically, the country remains calm, a collective relief abounds after the political upheaval of the preceding decade. A controversial law passed by a local council in February of this year, which forbade Britons settled in Londonderry from building on their own private lands was perhaps the only moment of controversy. It was a fleeting reminder of the tensions that flow beneath the surface both here and across the Irish Sea. The stationing of a garrison in Glasgow, looked ominous, particularly so as the British didn’t bother to hide their manoeuvres. There may be an ulterior motive to their granting us these liberties...”

May 1837: The government is pleased to report that a positive balance of trade has been fostered with exports of fish, cattle and fertiliser outstripping our imports of fruit, wool and grain. The improvement of our military doctrines continues.

1st Jan 1838: A tax increase was levied against the middle and lower classes in order to fund new education and administration initiatives on the part of the Conservative government. The state’s first ship “Lady Wicklow”, a steamer built in Dublin, arrived to great jubilation in the port of Cork on October 6th, the very day that a truce was declared between Britain and China. Reactionaries and liberals both made slight gains in the Senate, but nothing that could possibly trouble the “Blue Majority” as commentators have taken to calling the Senate.

The 1838 Potato Blight

July 1838: Potato blight has struck county Donegal and the government quickly steps in to assuage any panic and to tend to those affected- mostly poor Catholic farmers. However, word travels quickly of the blight and Ireland suffers a loss of prestige, with one Minister in Westminster remarking that “[The Irish] can’t even grow potatoes correctly when we are not there to help.”

Chapter 2: Succession and Democracy.

The years of 1838 to 1940 saw many changes both within and without. Queen Victoria was crowned in 1838, with both Prime Minister Roberts-Rowe and Lord Leith in attendance. Observers remarked at the obvious tension between the two men, uncomfortable in each other’s presence outside of diplomatic events. Rumours persist at home of blazing conflicts between the Irish-born Roberts-Rowe and Scottish-born Leith over the handling of the Donegal blight. A definite fracture was developing in the Conservative party. Liberals gained in the Upper House in both ’39 and’40.

On the European front, Prussia and Austria went to war, with Prussia demonstrating diplomatic nous by making peace with several of Austria’s allies before blood was shed.

The 1st of January 1840 saw the beginning of the election in Ireland- the first election after Home Rule passed. The divisions in policy (and some claimed, loyalty) in the Conservative Party lead to their shock defeat at the polls. Roberts-Rowe was succeeded as Prime Minister by Daniel O’ Connell, the man known as “The Great Emancipator” for his success in obtaining Catholic emancipation in the late 1820’s.

The 1840 election results

The new Whig government (a coalition of Liberal and Anarcho-Liberals) inherited a very healthy Finance Ministry. Exports of farming products were accelerating and the Bank of Ireland was now lending to several prominent nations in Europe. Capitalists, however, were finding it difficult to establish themselves, due to several factors, not the least of which was the vast majority of the available workforce were farmers or soldiers.

Chapter 3: “The Great Emancipator.”

Daniel O'Connell

The first term of O’Connell saw financial stability, particularly in the face of British belligerence around the globe- wars with Spain, France and China (once more) lead to concern that Ireland’s military potential would be threatened by other smaller nations. Though still firmly a satellite of Britain, the Irish had eyes on greatness. O’Connell set projects in Ulster and Leinster to advance industrialisation, particularly encouraging the construction of a glass factory. Looking on with little stature at Great and Secondary Powers colonising far-flung continents only hastened the government’s attempts to elevate Ireland.

From the diary of Peter O’Manhony, civil servant in Dublin Castle: 11/2/44

“I was over-joyed to receive a letter from my dear friend Cathal Donnelly, who has returned from the Colonies in India to take charge of the 1st Leinster Battalion. A greater soldier and leader cannot be found in this island or the next and his promotion to headquarters in Dublin suggests that we will be sharing a drink or six soon... “

“My department had to deal again with an outbreak of potato blight in Donegal, which we have been instructed to hush up about. The reoccurrence of the blight is a very discouraging thing, and one that I shall have to keep abreast of.”

“No sooner had the last one uprooted the Blues, another election has been called for December. The Conservatives are talking of amalgamating my Department of Administrative Affairs with Commerce and Agriculture, but I believe that to be mere hot air.”

Indeed, the election was to prove another triumph for O’Connell, who increased his party’s share of seats to 58%, roundly trouncing the Conservatives. As 1844 closed and 1845 dawned, the foundations for factories were finally being laid. Pro-business policies from the very beginning were now coming to fruition as the Capitalist entrepreneurs began to industrialise Ireland. With a population of just over eight million, O’Connell knew that Ireland’s fishing industry and potential colonies would be needed in the coming years to ensure Ireland standing space on the world stage. The future lay over the horizon, at sea.

Last edited: